Flying Lotus’s latest album, “You’re Dead!” is stunning. One of the best albums of music to be released this year. If you haven’t listened to it yet, get on it. Most of the tracks stuck with me in some way, but one that hit me hardest on the first pass maybe more than any of the other tunes, was “Never Catch Me,” a track both tight and breezy, introspective and pulsating, and featuring Thundercat and Kendrick Lamar on bass and vocals, respectively. I’m doing a cover it next month on the debut show of a new band I’ve started. We’ll have four horn players and a DJ. Live danceable concert jazz music. In the process of working with my arrangement, I transcribed “Never Catch Me” and wanted to share with you the brilliance of the chord progression that drives it forward.

Listen here (and watch the amazing video it is set to)

Let me first say that I’ve recently been touching up all my old transcriptions of Duke Ellington arrangements he did for Johnny Hodges’ 4-horn band in the 30s and 40s. One thing that occurred to me is that half of those charts, as hip and slick as they are, only have sometimes three chords. Some tunes maxed out around six chords. How could something so driving, so catchy, and so quintessentially swinging have so few chords? In comparison, most of the big band charts I transcribe from the same time period have dozens of chords. Anyway, keep this in mind…

After listening to the track linked above, how many chords would you guess are in that tune?

The answer is six.

And there are really only three different chord qualities (major, minor, and dominant). But otherwise only six. These six chords can hold your attention for almost five minutes, and they are worth taking a look at.

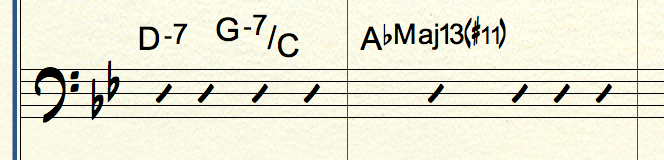

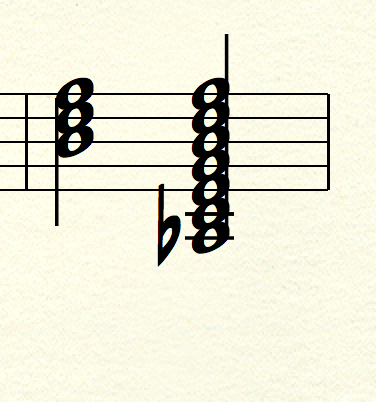

The track starts with a loop of the first three chords.

Those chord symbols are not 100% accurate, depending on what melodic idea is happening in the bar, but they get us close enough. We’ll talk about the discrepancies as we go.

First off, if I tell you I’ve got a D-, then a C-, what would be the 3rd chord to finish that pattern? There are two answers:

1) Bb-, continuing a pattern of minor chords descending by a whole step.

2) BbM, continuing a pattern of descending diatonic chords (in the key of Bb major, D- is the III-, C- is the II-, the BbM would be the IM)

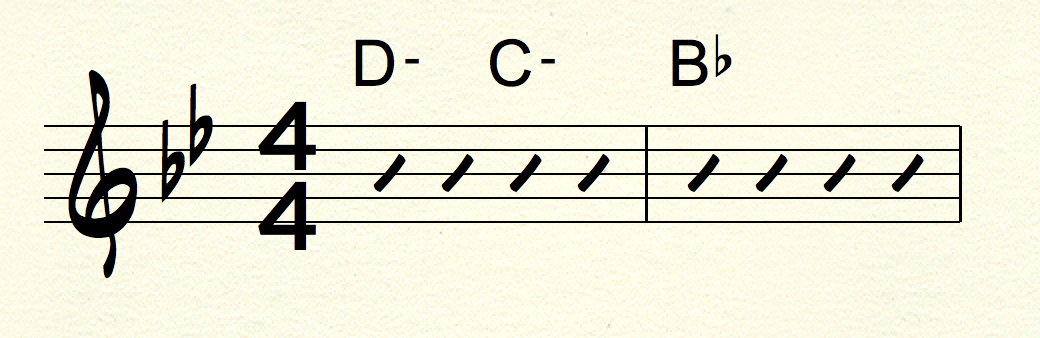

We’re going to work backwards from a simple progression to the one you see above. Step one includes taking option #2 above, a choice that we’ll discover later was not quite so arbitrary:

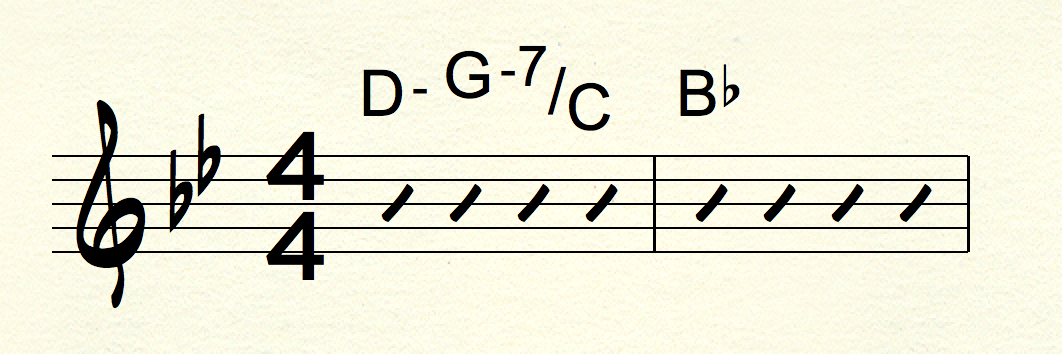

This is a simple diatonic chord progression that you might have heard in the age of Bach. Now we make a big leap forward to the 20th century and upgrade the C- to a variation on C-11, in a hybrid form:

The second chord now takes on a more modern jazz flavor. If you are unfamiliar with hybrid chords, do a little googling. The gist of it, though, is that you have a chord structure over a bass note that is not in the upper structure. The second rule is that you cannot have a note in the upper structure that is a third above the root note (in this case, an E or E flat, neither of which appear in the G-7). The resulting sound, called a hybrid, is deliberately ambiguous, as it is neither definable as a major or minor chord, even though the implication in this instance is that it is a variation of C minor; the context clues (the key signature in this case) give us that information, but without it we could make the case that it’s a stand in for C9sus4. See? Ambiguity! ANYWAY, it’s basically what you’re hearing in Never Catch Me, so let’s move on!

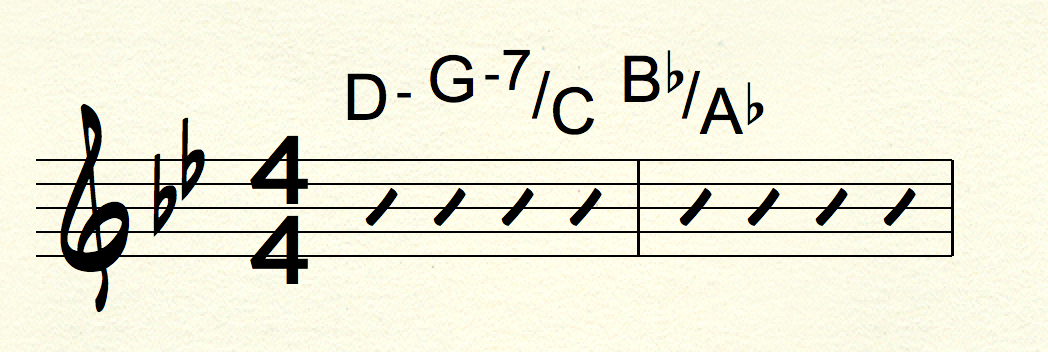

We decided that the diatonic pattern would lead us to Bb major. Now, what if you hit that chord with a Bb triad voicing, but put a bVII note in the bass? You’d have this:

Another hybrid chord! From there, what if you filled in the notes in between? You can hear a C and G for sure in that bar when you play through the track, so you have a full AbMaj13(#11). So, not a hybrid, even though we sort of arrived here through one.

This is basically how we got to the loop posted above. These are decisions made by the composer, but they are completely justifiable and functional.

The catch, though, is that this tune is probably not in the key Bb, but the key of G minor, both of which share the same key signature. That makes the chord progression analyze out as V-, IV-, bIIMaj. I’m basing that call on the fact that the two pivotal melodic notes in the piece are D and G. So I’d say the key is G-. BUT, a G- chord never comes up. The closest you get is the hybrid, the 2nd chord, and arguably the 3rd chord, as you could consider it a polychord of G-7 over Ab. There is no right or wrong answer, these are all possibilities, but either way, it’s a very clever loop.

So why does it hold our attention? Because it never resolves. It’s a perpetual tension machine. Even the first chord implies G- because of the melodic line in the piano, which includes a Bb pitch, even though in any harmony class you are told to avoid that tone on D- when it’s the III- chord. “That’s an unwanted tension, an avoid note!”

Unless it’s used for tension on purpose. I mean, watch the video; if that video doesn’t encapsulate “unresolved” I don’t know what does.

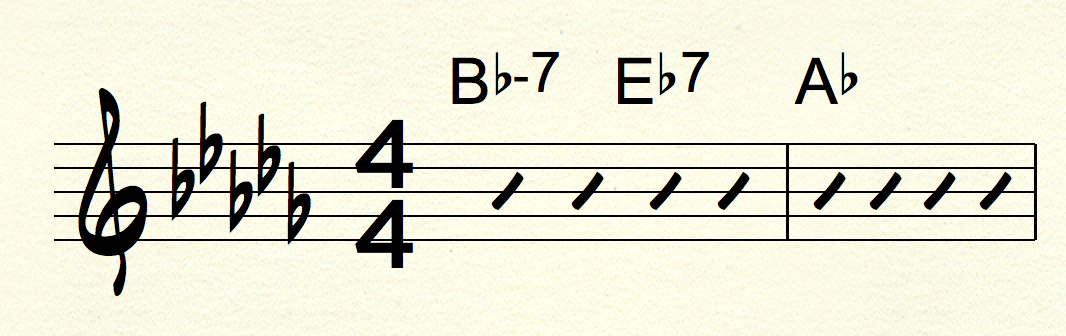

Moving on the the final section, before I show you what it is, let’s say we started with a simple II- V7 IM

NOTE: Pretend my key signature is minus one flat, I made all these graphics in the wrong key signature and boy is it tedious to make them again. So pretend it’s in the key of Ab. That’s the key we move to in the second half. Which is super clever because the first half’s loop kept ending on an Ab chord. So… does that mean we’ve been given a resolution? And wait, did my question way above about finishing the first pattern, wasn’t the other option to resolve to a Bb-? So certainly we’ve resolved… somehow… right? Let’s find out.

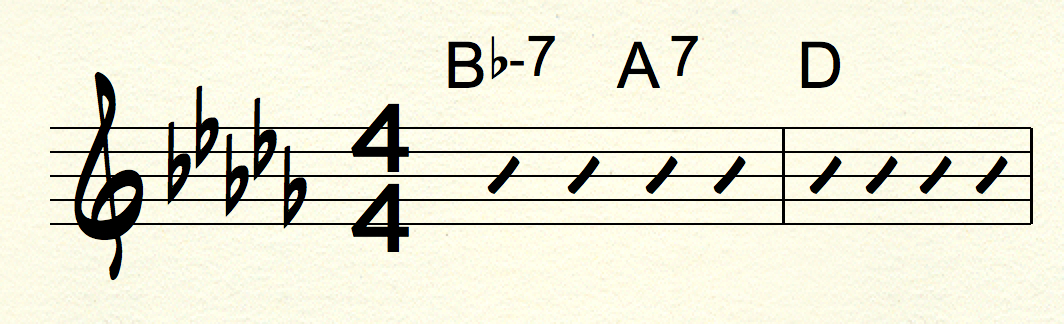

We start with the premise above. Incredibly diatonic, very simple, not much to say. Let’s have fun with it though, beginning with the 2nd chord, the Eb7. Let’s do a tritone substitution there. For those of you not following me, a tritone substitution is exactly what it sounds like. Basically any dominant chord can be replaced with a dominant chord a tritone away. It’s a simple reharmonization technique used to get some extra mileage out of a fairly predictable chord progression. Normally that Eb7 to A7 would mean that the A7 is labeled as subV7 and it continues it’s half step descent to land on Ab and all is well in the world. But what if you had that A7 function as a true dominant chord and have it resolve to D? That would lead us here:

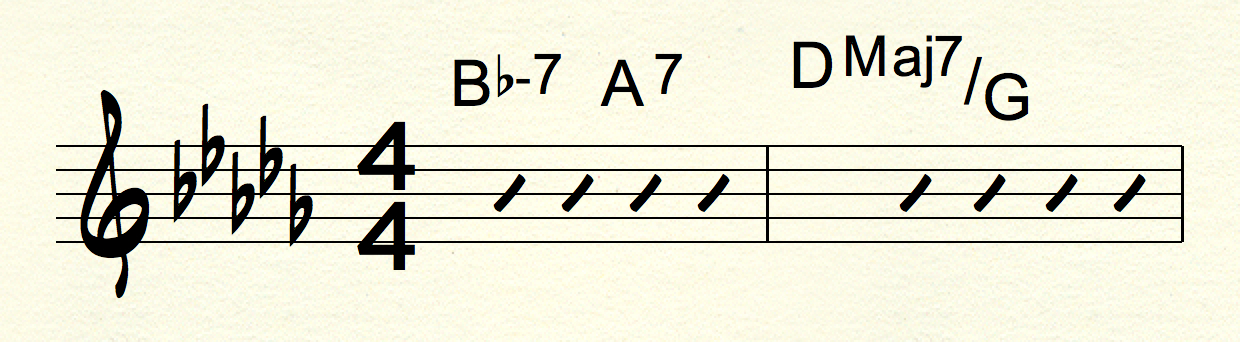

This is no longer a simple chord progression. Let’s say you added extensions to the D chord and made it a DMaj7, now you’ve come up with a cool sound. NOW, what if you treated it similarly to how you treated the Major chord in the first loop and added a new bass note? In this case, DMaj7|G. Some might argue that because you can hear the B natural pitch that it’s actually GMaj9(#11). Either way, you’re on a G majorish chord, another hybrid at the least, a full major chord at the most.

Further complicating things, Thundercat plays a bass line of 16th notes that has G D C# and F# in it, in that order. A wide-ranging riff that implies the DMaj7 and the G below it in a sophisticated, ambiguous, and definitely funky way.

What a cool chord to end on! Oh yeah, and if you argued that the intro was in G-, this section is ending on the parallel major, G Major. Whaaaat. Ok but wait, isn’t this second loop in the key of Bb-, or Ab Major, or something like that? You know what, let’s get to the heart of this:

Look, a lot of the terms we use to describe chords, we use those descriptions to better communicate with each other. When I give you a key, a chord, and a context, you (should) know what the chord scale is so that everyone can play notes together without clashing (by mistake that is) and no one clashes with written horn parts, etc etc. It’s easier than writing out full chord scales in every bar. Anyway, we use these terms when it’s simple enough, but how do you describe something that creeps by on the edge of functionality?

You don’t. You write out what it is, do your best with it, and just play. This track is a slowly-whirling ball of tension and non-resolution, and every two bars, just when you think you can settle in, they throw that big major / hybrid chord in there, and the cycle continues. If you are still reading and haven’t yet watched the video, you’re missing the point of this analysis. Seriously, watch the video. Listen to the rest of the album and listen to the themes Flying Lotus is working with.

Much of traditional jazz and bebop and pop music has cadences and resolutions and chances to breathe and relax and think, but on “Never Catch Me,” the track is designed so that you hold your breathe until the sound fades out entirely. It’s gripping, it’s entrancing, it’s mesmerizing. Like life, we don’t want it to end. Like death, there is no true resolution for those of us left behind.

This is not to say that other songs are inferior in any way. My point here is that Flying Lotus set out to create a specific idea and succeeded marvelously. And ultimately that is what analyzation, notation, etc… all of that exists for the benefit of the artist. All these tools are at our disposal in the quest to communicate. And this brings me back to Duke Ellington, because like Ellington, the brilliant simplicity in Flying Lotus’s music leaves room for the other stars to make magic.